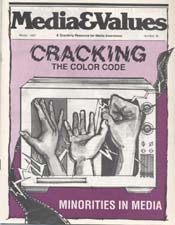

A Long Way to Go: Minorities and the Media

|

This article originally appeared in Issue# 38

|

During the September 18, 1986, televising of The $25,000 Pyramid, a most remarkable exchange occurred. In this popular game show two pairs of contestants compete. For each pair, a series of words appears on a screen in front of one contestant, who gives clues to try to get the partner to identify the correct word.

On that special day, the word gangs' came up on the cluer's screen. Without hesitation, he fired out the first thing that came to his mind: 'They have lots of these in East L.A." (a heavily Mexican-American area of Los Angeles). Responding at once, his guest celebrity partner answered, gangs."

Under competitive pressure, two strangers had immediately and viscerally linked "East LA" with "gangs" Why? What force could have brought these two strangers into such rapid mental communion?

The answer is obvious — the mass media. The entertainment media have displayed a fascination with Latino gangs, while the news media nationwide have given them extensive coverage. In contrast, the entertainment media have offered a comparatively narrow range of other Latino characters, while the news media have provided relatively sparse coverage of other Hispanic topics, except for such problem" issues as immigration and language. The result has been a Latino public image — better yet, a stereotype — in which gangs figure prominently.

Teaching Stereotypes

This singular but significant example has broad, important, even ominous implications for minority and other ethnic groups. First, whether intentionally or unintentionally, both the news and the entertainment media 'teach" the public about minorities, other ethnic groups and societal groups, such as women, gays, and the elderly. Second, this mass media curriculum has a particularly powerful educational impact on people who have little or no direct contact with members of the groups being treated.

Moreover, this special concern — the influence of the mass media on the public image of minorities — is only one of many complex features of the tortuous relationship between minorities and the media. Minorities have long recognized the media's power to influence their lives. And they have struggled to achieve greater influence over their own media destinies.

That's why Asian Americans protested against Michael Cimino's recent Chinatown-bashing movie Year of the Dragon. mats why black actors have protested against the paucity and lack of diversity of black film roles. That's why Native Americans have established both tribal and pan-Indian newspapers throughout the country. That's why Latinos have so vehemently protested the recent judicial decision to approve the Spanish International Communications Corporation's sale of five major Spanish-language television stations to Anglo-owned Hallmark Corporation, despite the existence of financially equivalent offers from groups with large Hispanic

Most minority media efforts, including protests, have focused on the area of media content. Minorities realize — supported by research — that the media influence not only how others view them, but even how they view themselves. So minorities and other ethnic groups have long attempted to convince industry decision-makers to seek better balance in news coverage of minorities and to reduce the widespread negativism in the fictional treatment of minorities by the entertainment media.

Likewise, they have clamored for the media presentation of better minority role models — in news, in entertainment, even in advertising — both to set standards for minority people and to reduce the deleterious stereotypes too long prevalent in the media. While progress has occurred, the media have not been consistently responsive or sensitive.

Decisionmakers

Part of the reason is that minorities have traditionally had only marginal presence and even less influence within the mainstream media. The national television visibility of Bryant Gumbel, Connie Chung, and Geraldo Rivera are of relatively recent vintage. While these breakthroughs are certainly welcome, the very exceptionality of such featured figures symbolizes the frustration that minorities still feel about the delays and continued slowness of progress within the mainstream news media. For example, currently only about 40 percent of the nation's 1,600 daily newspapers employ any minorities in editorial staff positions.

In the entertainment media, the successes of such stars as Bill Cosby, Oprah Winfrey, and Edward James Olmos, and for that matter even Richard "Cheech" MarIn and Tommy Chong, are cause for satisfaction. Minorities should also applaud the popularity of the movie version of The Color Purple, notwithstanding the controversy that it generated both within and outside of the black community. Likewise, minorities can take pride in the success of Wilson Wang's brilliant shoestring-budget film, Chan is Missing. Gregory Nava's low-budget sleeper, El Norte, a moving portrait of two Guatemalan undocumented immigrants, drew large audiences despite the fact that more than half of the dialogue was in Spanish and a Guatemalan Indian language, with English subtitles.

In heralding these advances, it still must be remembered that in six decades of Academy Awards, only three blacks (Hattie McDaniel, Sidney Poitier, and Louis Gossett, Jr.), two Asians (Miyoshi Umeki and Dr. Haing S. Ngor — Ben Kingsley is English of half-Indian ancestry), one Puerto Rican (Rita Moreno), and one Chicano (the half-Irish Anthony Quinn) have won Oscars for acting — Quinn twice. That makes an average of just over one per decade.

But the presence of a few prominent minority news people, television personalities and movie stars is less significant than the broader nature of the minority experience within the media industry. Gaining admission has not been easy, as obstacles to entrance remain.

And once inside the door, problems continue — personal isolation, difficulty in entering upper-level management, lack of influence, career hazards. Minority journalists often face the dilemma of balancing their social commitment to provide better coverage of minority communities against their fears of being "ghettoized" to the "minority beat" and thereby having their professional careers restricted. Minority actors find themselves caught between the need to find roles in which they can hone their craft and earn a living, and the recognition that many of these roles may contribute to public negative stereotyping.

Imagemaking

Such are the quandaries of marginality and the absence of power. For this reason, some minority people have opted to operate outside of the mainstream and form their own media. In this way, they have sought to select their own themes, express their own views, and influence their own public images. They have established their own newspapers and magazines, set up their own radio and television stations, created their own film production companies, and formed their own advertising agencies, often specializing in helping companies reach a "minority market."

As a result, periodicals now range from Ebony and Essence to Nuestro and Hispanic Business, from China Spring to the American Indian Talking Leaf. Many television and radio stations now provide programming in languages from Spanish to Korean. Ethnic people have been making alternative movies throughout the century, from Oscar Micheaux, the brilliant black director of the silent era to the Yiddish film industry of the 1930s to current minority film efforts.

But the road to media self-determination has not been easy. Most independent minority filmmaking efforts have collapsed due to the lack of financial solidity needed to create consistently high quality productions. Some minority publications have achieved economic success, but even more have had limited longevity. Radio and television stations may broadcast in many languages, but ownership — and therefore control over news and editorial policy — often does not rest in minority hands. Such rousing rhetoric as "minority media self-determination" may foster utopian dreams, but the economic realities of survival and control — the necessary conditions for ongoing media power — are often nightmares for minority media entrepreneurs.

Minorities have long been aware of the influence of the mass media on their lives and have struggled to increase their own impact on the media. While the results have often been frustrating and depressing, there have been victories and successes to which minorities can point and emulate. With increasing media experience and sophistication, minorities are determined to expand their media influence, as they are expanding their physical presence in our increasingly multiethnic society.